EPENDYTIS MAY 2012

From Neolithic Greece to Easter Island

Vivi Vassilopoulou

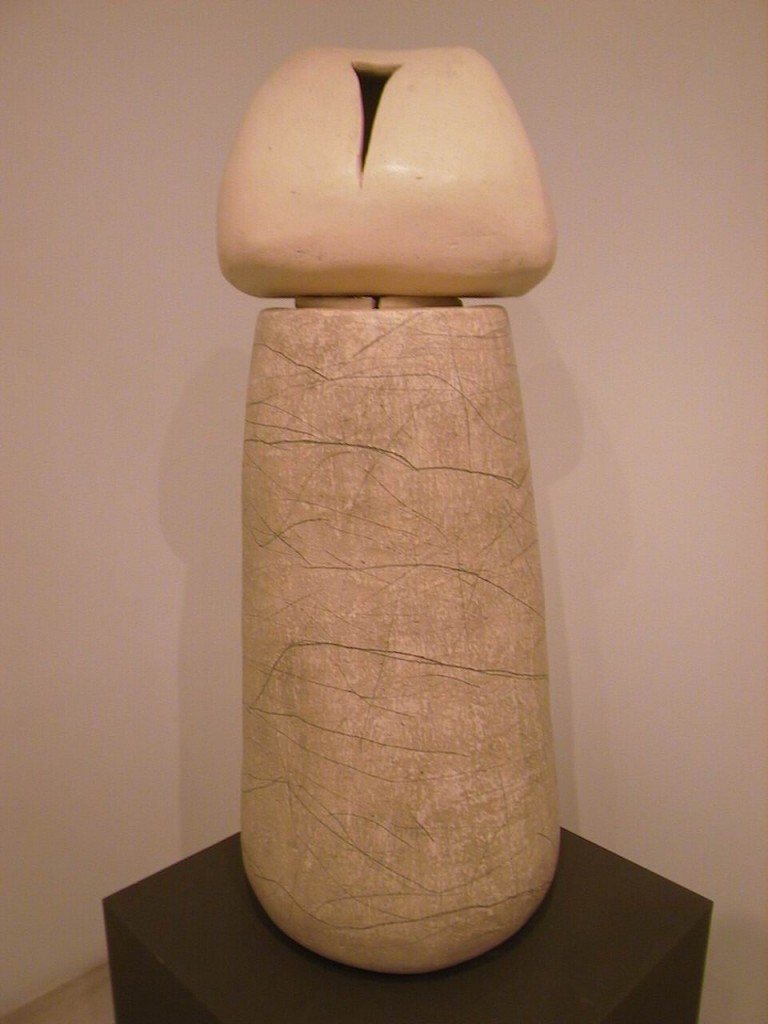

“In these abstract ceramic forms which emphasise their schematic immobility more than their meaning, a deep vertical slash allows the gaze to penetrate the dark field and the imagination”. This is true. And the imagination flies from Xenokratous Street and the Medusa Gallery to Easter Island, seeking to discover the timelessness of such works, their secret agreement, their invisible relationship, their common traits and their differences which set them apart in terms of form, material, spirit, space and method. And also in terms of apparent intentions. Apparent, because the hidden ones and the subconscious may be common to all; to leave a Signal on Earth, a Body/Signal in the ancients’ sense of the word. A vertical mark along the trace of our existence; a totem. It is true that we often describe artists as creators, yet this time I believe I was able to hear the silence of creation as only the mind can hear and see, as Maria Vlanti described their Beginning.

“I had moulded these forms lying on their side”, she said, “and I was looking for a way to make them stand on their feet”.

The rest of the story we know. Her hands gave birth to the form, and the form assumed the air and the posture of a figure standing upright on Earth.

We are already among expressive figures with their own personal characteristics, with a right to converse among themselves and with the viewer but above all with painting, since their matiére is special, and with sculpture, since their texture calls out to be touched and caressed.

“And how can they stand like that?” I asked. It is thanks to the weight of timelessness, to their specific gravity and to a metal rod inside them – their own rigid spine which seems to stand firm against time and definitions.

We are now going through a phase in which the Cultural Olympics provides shining examples, at least in the area of spectacles, while the culture of cultures keeps us revising and redefining our views on it, and not only as far as major projects are concerned.

I would claim with certainty that the works of Vlanti contribute in their own way to this culture of cultures, from Neolithic Greece and today’s united Europe to the remote island we mentioned at the beginning.

ESTIA MAY 2012

Krista Konstantinidi

The austere ceramic forms of Maria Vlanti at the ‘Medusa’ could provide an answer to the question of how can a contemporary artist create totally new forms with references across the entire history of art. On entering the room, a well laid-out set of imposing static forms instantly attracts you. Prehistoric figures of religious totems or Cycladic statuettes? It was certainly not the artist’s intentions to copy or even to imitate any of these. For Vlanti the focus seems to be on a spiritual quest across the millennia. So she employs this timeless power of the minimal that characterises her works to transport the viewer beyond the boundaries of time.

Aside from the austerity of forms, I was impresses by the …big, ‘baked’ material which acquires the texture of bodies which had once lived. The perceptive viewer will discern on them the traces left by cavemen on the rock, but also the random scribbling that the American expressionist Cy Twombly carved on his canvases not long ago. The sculpture of Vlanti brought to my mind a journey to the depths of history in a modern vehicle… (7 Xenokratous St, until June 15).

The Ceramic Morphotypes of Maria Vlandi

What impressions would the visitor to the Museum of Cycladic Art have, were he to catch a glimpse of Maria Vlandi's austere ceramic forms in the adjacent hall? Could he imagine them to be clay Cycladic statuettes, enlarged to life size but with less angular features, standing motionless before him on bell-shaped or broadened pedestals, silent and imposing? Maria Vlandi may not have posed this question when she set out to try new forms; it may, rather, spring from an overview of the works displayed as a whole, but the viewer will perceive that in highlighting a chapter from our cultural legacy, the artist is testing her power of imagination and translating history into the images of modern man. As familiar as we may have become with the configurations of both static sculpture and mobile constructions, there still remains within us - particularly those of us who are artists - the primary concept of sculpture, which starts from abstractly formed figurines and goes all the way to integrally structured works. When Maria Vlandi succeeded in extending her quest from small three-dimensional ceramic shapes to large clay forms standing free in space, she discovered the hieratic stateliness inherent in the strict precision of the prehistoric xoana and Cycladic statuettes unearthed by archaeologists. Xoana, ritual wooden effigies in human form that represented the deity in the inner sanctum and to which the Cretan, Cycladic and Mycenean peoples offered the stylised figurines, sanctifying their existence, cast a spell with their detachment from reality. This element of magic imbues the contemporary forms rendered by Maria Vlandi. The artist does not invite us to view them as free copies or as an intellectual transcription of the Bronze Age statuettes, but rather to wonder at the power that pervades their abstractive moulding, conveying emotions and intervening in the individual viewer's psyche in any era. The new work presented at Maria Dimitriadi's Medusa Gallery includes abstractive clay forms, the static shaping of which must be stressed over their meaning. Contemplating each of them separately, we find an eloquent response to the question of how an artist of today can create new forms that allude to the history of art, while remaining constantly open to information and personal experience. From this point of view, I could maintain that it is a harsh answer with an intriguing subconscious philosophical aspect and a structured aesthetic position in the fleeting imagery of the contemporary world. The extremely rapid flow of things mixes the images of works of art with those of advertising. The eyes may thus be enriched by experience, but human consciousness is impoverished in relation to both the quality of the aesthetics and the quantity of knowledge, leading us to conclude that everything is interesting, some things more and others less. In this blend, works lose part of their solid, compact structure, and advertising images acquire something of the nature of works of art. In 1976, the Czech artist Jiri Kolar (b. 1914) fashioned his own variation with three Cycladic Heads displayed on a single stepped base. Each head constituted a commentary on the features of contemporary civilisation. He placed a large spot on the forehead of one and a black blotch for the mouth, on the second he painted the Milky Way and on the third he stuck a round piece of cardboard bearing microchips. The work belongs to the Albright-Knox Art Gallery collection to which it was donated by the Evelyn Ramsey Cary Foundation. In my view it constitutes an "advertising" version of an important cultural product, in which spirituality and history are replaced by irony and metaphor. I refer to this specific example of the Czech artist's work in order to support the view that if cultural memory is not imitated, but instead new morphotypes that comprise elements of cultural memory containing timeless elements are constructed and moulded, we may consider Maria Vlandi's fresh aesthetic offering to be both original and thought-provoking. Each separate three-dimensional clay form has three parts: a long and narrow compact conical or oval trunk standing on a pedestal or on the ground, a hint of a neck expressed as a small ceramic mass of irregular shape, and a third widened, cylindrical or irregular part for the head. These are absolutely unique forms of normal dimensions. Their singularity is manifested in the strong patterns used by the artist in the place of facial features. A deep, vertical cut allows the gaze to enter a field of darkness and the imagination to form the impression of a deity that expresses the void. The opposite, a circle penetrated by the gaze suggests a deity of plenitude. Fullness and emptiness are the two principles - male and female - that are always expressed together in the universe, as we are told by the initiates of esoteric philosophy. An inverted triangle filled with small slanted broken straight lines in relief suggest the pubic area, giving the impression of a goddess of love. Demarcated small and larger elongated parallelograms filled with broken straight lines in relief also refer to fertility. A stellar symbol in relief (the sun?) with both large and smaller rays that spread over the broad, curved surface of the head refers to a symbolic deity of light, truth, power and superior authority. It is clear that in Maria Vlandi's work, the law of inner unconscious association has been at play, for we must accept her view that she had no intention of imitating or reflecting on Cycladic sculpture. This law allowed her to impart life, constructing, firing and assembling irregular ceramic shapes, as opposed to the methods of Cycladic sculptors who removed pieces from the marble. If the resulting form of the statuette was determined through the process of chiselling, in Vlandi's work the factor of chance co-exists with the moulding of the clay and its firing to reach the desired result. The asymmetry of the work succeeds in conveying the impression of continuity and immediacy. Through their natural dimensions, her forms give rise to a new sense of grandeur, appearing to be so filled with fresh concepts and meanings that we may speak of a continuation of intellectual seeking distanced from the laxity of industrial and advertising ideology. Nikolas Kalas has written that "communication through perception and insight means highlighting what is hidden."1 Without superfluous embellishment, Maria Vlandi sends us her messages symbolically, so that viewers may relate to the new symbols and signs of their own time and space.

Yiannis Kolokotronis Asst. Professor of History of Art, Xanthi Technical University